Carabiners: 101

Carabiner Blog

I have always thought of the carabiner like an offensive lineman in football, when the job is done well it goes unnoticed. Admittedly, up until recently I have not put much thought into these metal ovals that have saved my life countless times. Luckily, I work with some of the most knowledgeable gear heads in the gorge and I did some investigation and explored the wonderful and diverse world of the carabiner. This blog is for those who’ve trusted the same basic biners for years without thinking twice. It’s time to give these unsung heroes their due.

To lend some credibility to this research I have consulted three of my most knowledgeable coworkers: Kenny Parker (Local climbing legend), Jovany Cuesta (Gear guru), Race O’Neal (Super strong climber and guide certified).

Best gear advice in the gorge right here!

Section 1: Material

Carabiners come in all shapes and sizes, but almost all are made from one of two materials: steel or aluminum alloy.

Steel carabiners are incredibly strong and durable, but significantly heavier. They’re generally impractical for most climbing applications, except in fixed setups or as belay biners where weight isn’t a major concern.

Aluminum carabiners are the go-to choice for most climbers. They’re much lighter, more corrosion-resistant, and last a long time under normal climbing conditions.

Unless you have a very specific need, aluminum is the ideal choice for almost all recreational climbing purposes.

Section 2: Shape

There are three main carabiner shapes you’ll encounter: oval, D-shaped, and pear-shaped (HMS).

Oval carabiners are symmetrical and often used for aid climbing, racking gear, or with pulleys. The shape helps gear stay centered, but they are typically heavier and weaker than the alternatives.

D-shaped carabiners are the most versatile. The asymmetrical design redirects force toward the spine, making them stronger and less likely to cross-load. This is the shape most commonly used for quickdraws and general climbing use.

Pear-shaped (HMS) carabiners have a wide top originally designed for the Munter hitch. Today, they’re ideal for belaying and rappelling due to their large internal space. Some versions include a spring-loaded divider that separates the belay loop and device, keeping both secure and in proper alignment.

*This HMS Carabiner has a spring-loaded divider which can be super helpful when belaying!

Section 3: Gate Types

Locking Carabiners

Locking carabiners come in two primary varieties: screw-lock and auto-lock.

Screw-locks are simple, reliable, and easy to operate—but only if you remember to screw them shut. The main risk is human error.

Auto-locks (such as twist-lock or triple-action gates) reduce that risk by locking automatically. However, they can occasionally open under specific pressure or twisting if not well-designed. Triple-action gates offer added security but can be difficult to operate with one hand.

Non-Locking Carabiners

The main debate for non-lockers is between wiregates and solid gates.

Wiregates tend to be lighter and because of that they avoid excessive gate flutter on falls (this happens when the rope abruptly comes to tension and the gate briefly “flutters” open). However many people do not like the feeling of the wire gate and avoid them for that reason.

Solid gates are more rigid and traditional, sometimes preferred for their feel and familiarity. A downside of this style is that the greater mass increases gate flutter, potentially weakening the system during a fall. They also tend to be slightly more expensive.

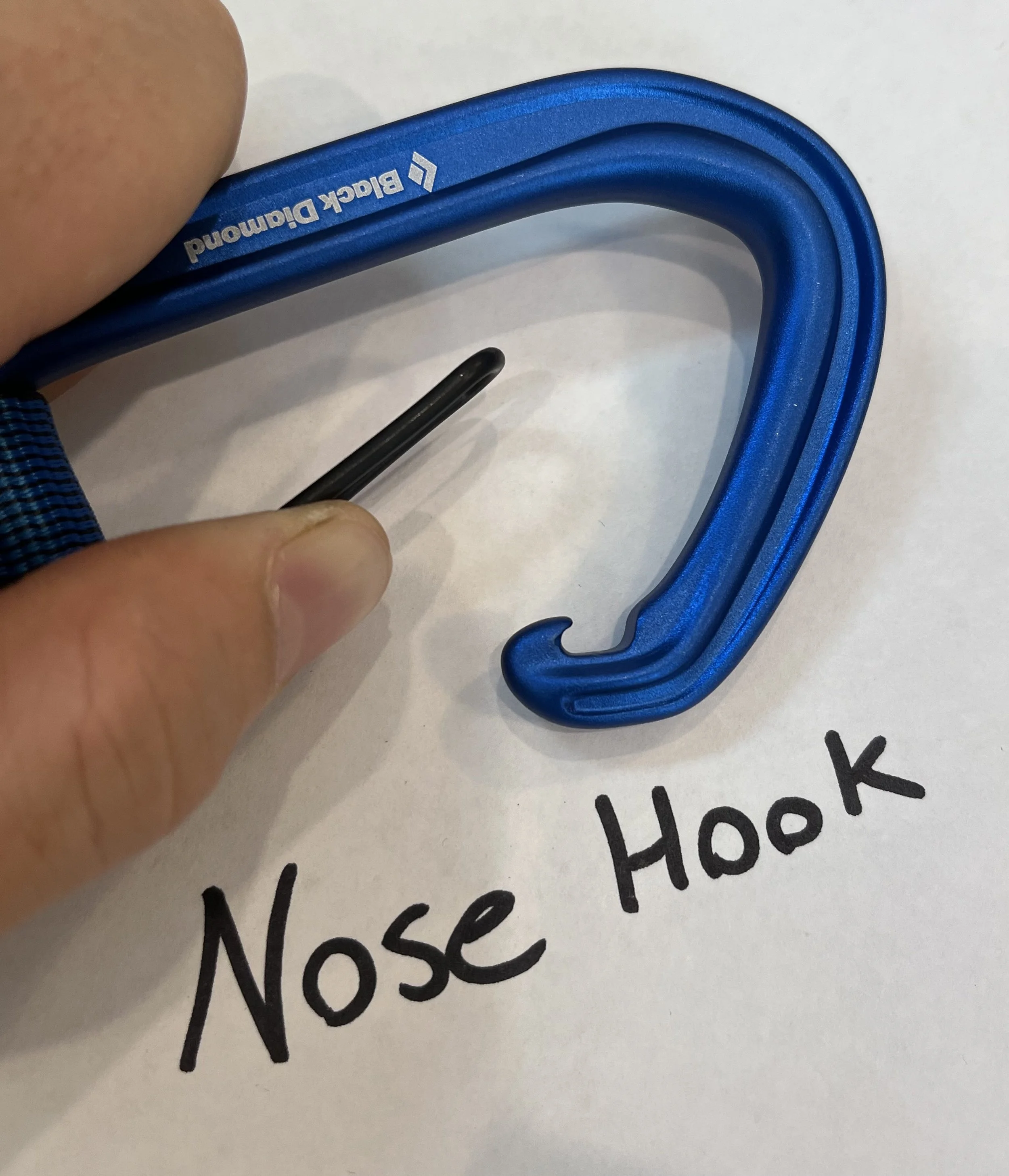

Perhaps the bigger issue isn’t the gate style but the nose design. Many cheaper carabiners feature a nose hook, a small notch where the gate latches. These notches can snag ropes or bolts while cleaning or unclipping, which is not only frustrating but potentially dangerous.

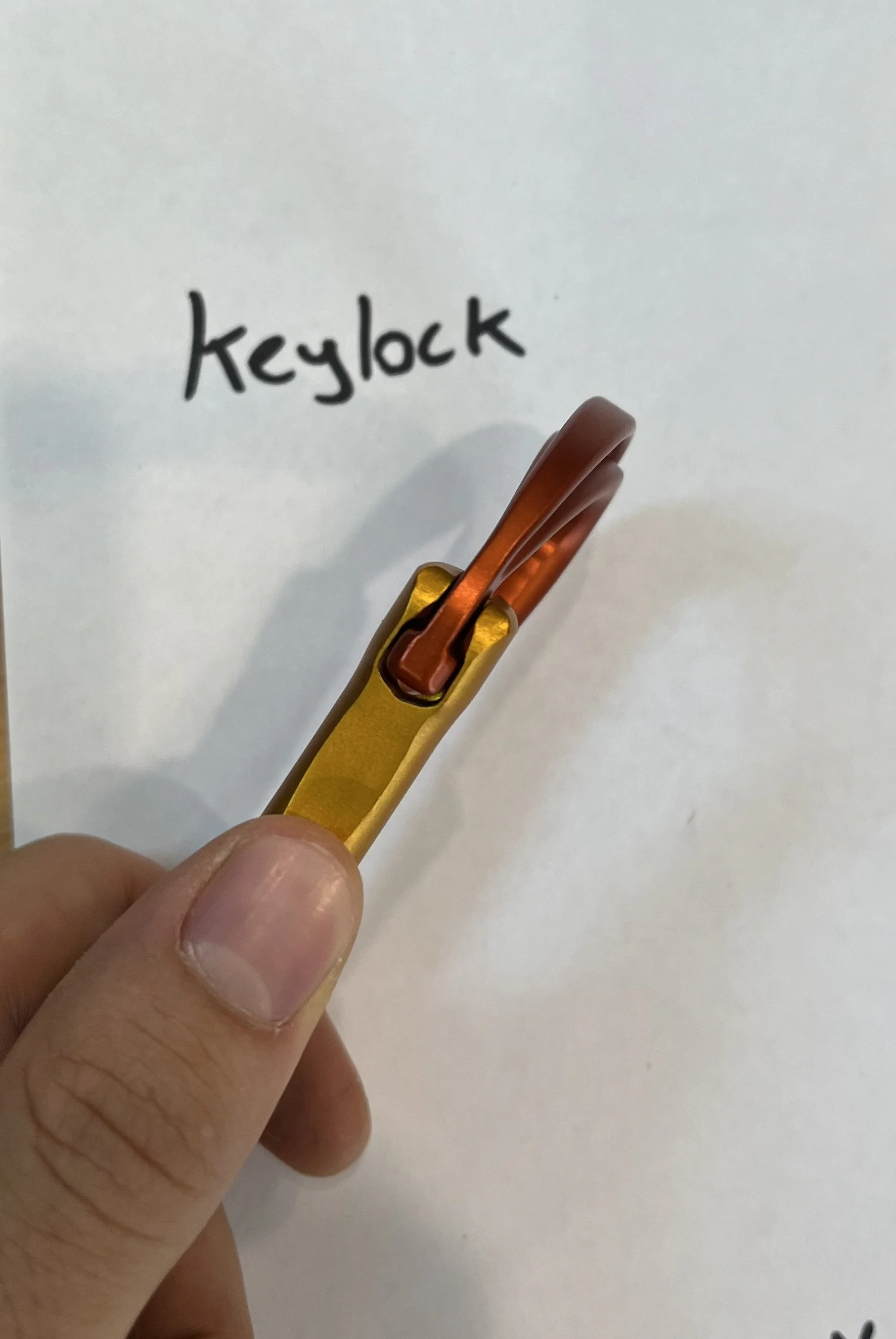

If a carabiner gets "nose-hooked" on an anchor point, it may only support 10% of its rated strength. For this reason, many climbers now seek keylock carabiners—those with a smooth, notch-free nose. If you can, spend the few extra dollars and choose a keylock. Keylock carabiners are also less prone to gate flutter compared to the nose hook design.

Wire gate with a nose hook design.

Keylock style with a solid gate.

Section 4: Retiring Carabiners

Carabiners are some of the most durable tools in your kit, but they’re not invincible. It is important to consistently clean and lubricate your carabiners, but still, over time and especially with heavy use, they may need to be retired.

Here are a few general guidelines to follow (but always check with the manufacturer’s recommendations):

Worn grooves in the basket or rope path can weaken the structure.

Sharp edges, even tiny ones, can damage your rope and become a serious hazard.

If a gate won’t close properly, even after cleaning and lubricating, it’s time to let it go.

As with all safety gear: when in doubt, retire it.

Coming Soon

Stay tuned for next month’s blog, where we’ll cover creative ways to retire your old climbing gear!

This month’s blog post is by Rhett Cosgrove. I am a summer intern here at Waterstone and will be returning to college at William and Mary in the fall.